|

||||

|

Anti-Design

By Charles Moffat - August 2011.

(Note: Although Anti-Design ended in 1980, this page includes examples of objects after 1980 to show how Anti-Design continues to influence contemporary designers today.) Anti-Design was a design flow and style art movement originating in Italy and lasting from the years 1966 - 1980. The movement emphasized striking colours, scale distortion (ie. giant chairs that make you look small), and used irony and kitsh. The function of the object was to subvert the way you thought about the object. In architecture this was also known as the Radical Design period. The design movement was a reaction against what many avant-garde designers at the time saw as the perfectionist aesthetics of Modernism. The Modernist designers placed emphasis was on style and the aesthetics of good form by many leading manufacturers and celebrated designers (some of whom were being paid big bucks in the process).

This sense of dissatisfaction with the increasingly lack of the social relevance of design for the sake of greed led Italian designers to stage a revolt. These design rebels increasingly aired their grievances during the late 1950s and into the 1960s. However Anti-Design didn't officially start as an art movement until 1966. Ettore Sottsass Jr. was a key spokesman of the Anti-Design movement once it took off and grew in popularity, as were the Radical Design groups Archigram (a British architecture magazine which emphasized alternative thinking and futurist architecture) and Superstudio (an architecture firm founded in 1966 in Florence, Italy). They were all expressing their ideas by producing furniture prototypes, exhibition pieces, and publication of manifestos full of ideas that are still considered revolutionary even today.

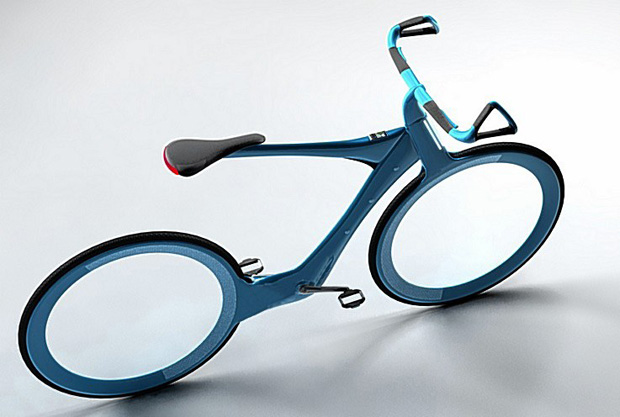

The Anti-Design movement sought to harness power of design to create objects and living quarters that were unique rather than embracing style, mass production, consumerism, sales and greed. Their designs were meant to be functional, not necessarily beautiful. Where Modernism followed the idea of objects should be permanent, Anti-Design rebels felt objects should be temporary, as quick to throw away and be replaced by something new and more functional. This would certainly mean consumerism and profits if people keep coming back for more, but the message was very different. Anti-Designers wanted people to THINK about the objects they were buying, even if they ultimately threw those objects away. The Modernist palette was generally blacks, whites and greys, simplicity and materials were chosen for their durability. In contrast the Anti-Design rebels explored the rich variety of colours, decorative elements and materials. Lastly, where Modernism believed in the adage ‘form follows function’, Anti-Design used the expressive potential of kitsch, irony, and distortion of scale... These characteristics would later become the hallmarks of Postmodern design and influence Memphis design. Below: A bicycle design influenced by Anti-Design.

Anti Design ArtistsAnti-Design rebels felt that design should mesh with humanity's uniqueness, not the other way round. Modernists had used design to reform lifestyles in order to make people healthier, more productive and so on. Anti-Design had a more modest, self-effacing conception of the role design should play. Modernists wanted to make objects that would fit in with modern lifestyles and be useful, but unobtrusive. Anti-Designers went the other way to create objects which were both useful but stood out for their bizarrity. In 1972, the Museum of Modern Art in New York held an international exhibition entitled "Italy: The New Domestic Landscape". This was a show of contemporary Italian designers, focusing heavily on the radical “Anti-Design” movement. Below are some of the designs that were exhibited at the MOMA exhibition.

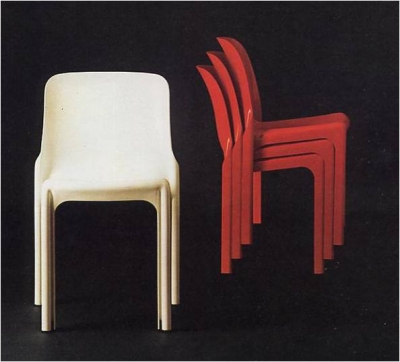

Vico Magistretti (1966) The Selene chair by Vico Magistretti (1966) was made of reinforced polyester [Fig. 1]. Within Anti-Design, there was a major preoccupation with space and storage. They often tried to make their designs collapsible or stackable and easy to store. This chair could be stacked in order to save space. With radical design like this, the challenge was always to find a manufacturer that would take the risk of producing it. This piece was manufactured by Artemide. Modernist designers were often treated as heroic figures, and they encouraged that by publishing manifestos and autobiographies. Anti-Design tried to break down the image of the heroic designer. One way of doing that was to allow the user to participate in the design. Stackable plastic chairs have become so common now we have almost forgotten their origins.

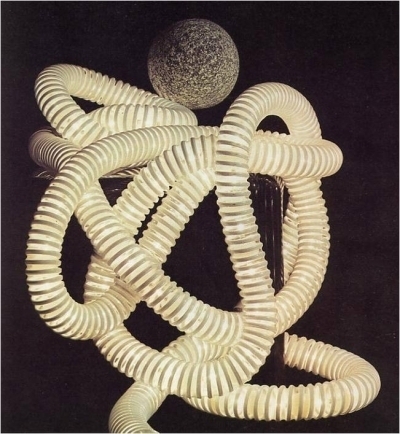

Gianfranco Frattini and Livio Castiglioni (1969) The Boalum flexible lamp (1969) by Gianfranco Frattini and Livio Castiglioni is an example. This was manufactured by Artemide. It consisted of a long plastic tube with light bulbs wired up inside, so it formed a luminous tube. The form is indeterminate – it can be manipulated by the owner. This helps to break down the persona of the heroic designer by allowing the user to determine the form, at least to some extent. Anti-Design responded to the ways in which Modernist designs were consumed and discussed in the design press. They were worshipped almost, and there was a sense that people had to adapt to suit the design, not the other way around. Anti-Design tried to break down that excessive veneration of the object.

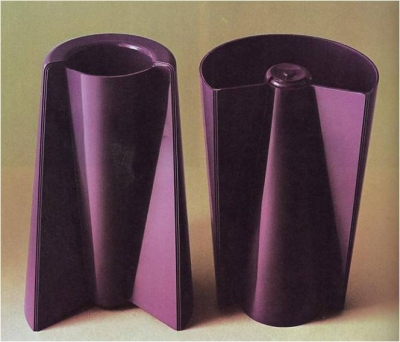

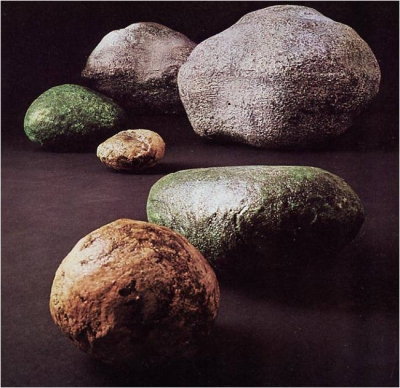

Enzo Mari (1969) Another example is a Reversible Vase by Enzo Mari (1969). It was made of ABS plastic and manufactured by Domese. It can be displayed upside down, which makes the form adaptable. This suggests that the Modernist idea of the type-form – the perfect design solution – is impossible to achieve. It was typical for anti-design to demonstrate manoeuvrablility and flexibility, so that they would be compatible with modern lifestyles. Piero Gilardi (1967) Piero Gilardi produced a piece called I Sassi (1967), which means “the rocks.” These are actually chairs made of polyurethane. They were manufactured by Gufram. Here the form disguises the function – they look like rocks. So they’re imitating a natural object. Now obviously, a rock is hard and durable. These qualities are totally at odds with the function of a chair, which is supposed to be soft and comfortable. So again this is defying Modernist functionalism. It makes the function illegible.

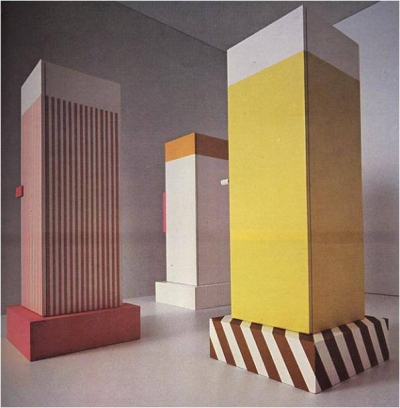

Ettore Sottsass (1966) Ettore Sottsass designed a series of cupboards (1966). Sottsass was a young designer, who was then at the start of his career. These cupboards are made of plywood. They’re paradoxical: they look like strange, inscrutable monoliths, like obelisks, but they’re covered with deliberately tacky plastic laminates. The decorative surface seems to undermine the stern form. This challenges the pomposity of Modernist design.

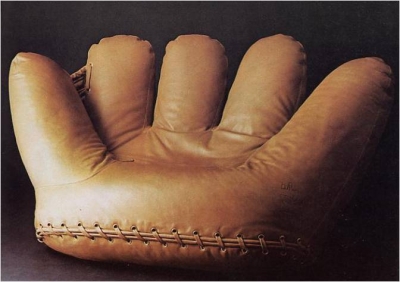

Paolo Lomazzi (1970) The famous Joe Sofa (1970) was designed by Paolo Lomazzi and named after Joe Colombo, a legendary Italian designer. It was made of polyurethane and covered with leather. This was manufactured by Poltronova. It looks like a giant baseball catcher’s mitt. Like postmodernist design, it’s an overblown symbol designed to communicate on a very basic level. It suggests that forms don’t have to be invented, they can just be recycled.

The Anti Design Studios

Superstudio • Founded in Florence in 1966 by Adolfo Natalini and Cristiano Toraldo di Francia. • Disillusioned with Modernism, which had dominated architecture and design since the 1920s. • Torelado di Francia wrote: "It is the designer who must attempt to re-evaluate his role in the nightmare he has helped to conceive." • Natalini: "In 1969 we started designing negative utopias like Il Monumento Continuo, images warning of the horrors architecture had in store with its scientific methods for perpetuating standard models worldwide. Of course, we were also having fun."

|

|

|||

|

|

||||

|

Archizoom (Associati) • Founded 1966 in Florence by Andrea Branzi. • In 1972, they declared the ‘right to go against a reality that lacks meaning . . . to act, modify, form, and destroy the surrounding environment.’ • No-Stop City (1969), an ironic critique of Modernism. • Branzi: ‘The real revolution in radical architecture is the revolution of kitsch: mass cultural consumption, pop art, an industrial-commercial language. There is the idea of radicalizing the industrial component of modern architecture to the extreme.’ Studio Alchymia • Founded by Alessandro Guerriero in 1976. • ‘Alchymia’ means alchemy, the pseudo-scientific practice that tried to turn base metal into gold. The name suggests that the group was turning the banal, everyday objects of mass culture into design. • Meligete cabinet, designed by Alessandro Mendini (1984). • Atomaria lamp by Mendini (1984).

Memphis • Founded by Ettore Sottsass in 1981. • The name is a reference to Memphis, Tennessee (home of Elvis Presley) and the ancient Egyptian city of Memphis – simultaneously referring to modern popular culture and to ancient/classical culture. It was also said to be inspired by the Bob Dylan song Stuck Inside Of Mobile With The Memphis Blues Again. • Published Memphis, The New International Style in 1981 – the title was a riposte to Modernism. • Drew inspiration from Art Deco, Pop Art and 50s kitsch. • Memphis embraced the ephemeral nature of fashion: “We are all sure that Memphis furniture will soon go out of style.” • Sottsass: “It is no coincidence that the people who work for Memphis don’t pursue a metaphysic aesthetic idea or an absolute of any kind, much less eternity . . . Today everything one does is consumed. It is dedicated to life, not to eternity.”

|

||||

|

|

|

||