| PABLO PICASSO

The Art History Archive - Cubism

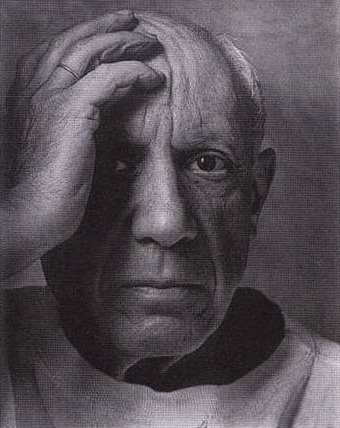

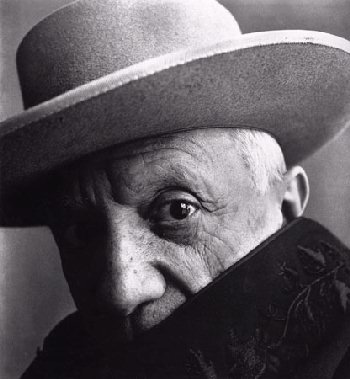

The Most Famous Artist of the 20th CenturyBiography by Charles Moffat. Full Name: Pablo Diego José Francisco de Paula Juan Nepomuceno María de los Remedios Cipriano de la Santísima Trinidad Clito Ruiz y Picasso Born October 25, 1881 - Died April 8, 1973. “Everyone wants to understand art. Why don’t we try to understand the song of a bird? Why do we love the night, the flowers, everything around us, without trying to understand them? But in the case of a painting, people think they have to understand. If only they would realize above all that an artist works of necessity, that he himself is only an insignificant part of the world, and that no more importance should be attached to him than to plenty of other things which please us in the world though we can’t explain them; people who try to explain pictures are usually barking up the wrong tree.” - Picasso

The Beginning, Childhood and Youth: 1881-1901Pablo Ruiz Picasso was born on October 25, 1881 to Don José Ruiz Blasco (1838-1939) and Doña Maria Picasso y Lopez (1855-1939). The family at the time resided in Málaga, Spain, where Don José, a painter himself, taught drawing at the local school of Fine Arts and Crafts. Pablo spent the first ten years of his life there. The family was far from rich, and when 2 other children were born -- Dolorès ("Lola") in 1884 and Concepción ("Conchita") in 1887 -- it was often difficult to make ends meet. When Don José was offered a better-paid job, he accepted it immediately, and the Picassos moved to the provincial capital of La Coruna, where they lived for the next four years. In 1892, Pablo entered the School of Fine Arts there, but it was mostly his father who taught him painting. By 1894 Pablo’s works were so well executed for a boy of his age that his father recognized Pablo’s amazing talent, and, handing Pablo his brush and palette, declared that he would never paint again. In 1895 Don José got a professorship at “La Lonja”, the School of Fine Arts in Barcelona, and the family settled there. Pablo passed the entrance examination in an advanced course in classical art and still life at the same school. He was better than senior students doing their final exam projects. “Unlike in music, there are no child prodigies in painting. What people regard as premature genius is the genius of childhood. It gradually disappears as they get older. It is possible for such a child to become a real painter one day, perhaps even a great painter. But he would have to start right from the beginning. So far as I am concerned, I did not have that genius. My first drawings could never have been shown at an exhibition of children’s drawings. I lacked the clumsiness of a child, his naivety. I made academic drawings at the age of seven, the minute precision of which frightened me.” - Picasso. In 1896 Pablo’s first large “academic’ oil painting, “The First Communion”, appeared in an exhibition in Barcelona. His second large oil painting, “Science and Charity” (1897) received honorable mention in the national exhibition of fine art in Madrid and was awarded a gold medal in a competition at Málaga. Pablo’s uncle sent him money for further study in Madrid, and the youth passed entrance examinations for advanced courses at the Royal Academy of San Fernando in the city. However, he would abandon the classes by that winter. His everyday visits to the Prado seemed much more important to him. At first, he copied the old masters, trying to imitate their style; later they would be the source of ideas for original paintings of his own, and he would re-arrange them again and again in different variations. Picasso’s time in Madrid, however, came to a sudden end. In summer 1898, catching scarlet fever, he came back to Barcelona, and then, to recover his health, he travelled to the mountain village of Horta de Ebro and spent long time there to return home only in spring 1899. In Barcelona, he frequented Els Quatre Gats (Catalan for "The Four Cats"), a café, where artists and intellectuals used to meet. He made friends, among others, with the young painter Casagemas, and the poet Sabartés, who would later be his secretary and lifelong friend. In Quatre Gats Picasso met vivid representatives of Spanish modernism, including Rusinol and Nonell and he was very enthusiastic about new directions in art. This was the point when he said farewell to “classicism” and started his long-lasting search and experiments. His relations with his parents became strained, as they could not understand and forgive him his "betrayal of classicism". In October 1900 Picasso and Casagemas left for Paris, the most significant artistic center of the time, and opened a studio in the Montmartre. The art dealer Pedro Manach offered Picasso his first contract: 150 francs per month in exchange for pictures. His first Paris picture was “Le Moulin de la Galette” (Guggenheim Museum, New York). In December, he departed for Barcelona, stopped in Málaga, and finally arrived in Madrid where he became co-editor of the magazine Arte Joven. However, by May 1901 he was back in Paris. This restlessnessa and constant travel from one corner of Europe to another continued throughout his life, and though he would slow his pace in his latter years, he never did finally settle down.

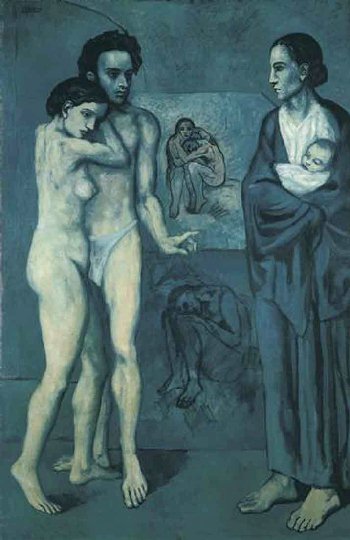

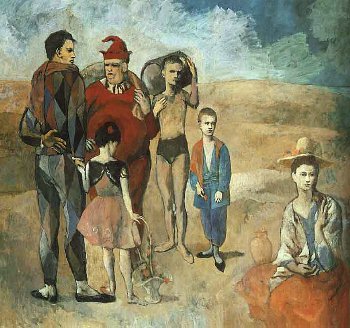

The Blue and Rose periods: 1901-1906In February 1901 Picasso’s friend Casagemas committed suicide: he shot himself in a Parisian café because a girl he loved had refused him. His death was a great shock to Picasso, and the painter would return to it again and again in his art: he painted the Death of Casagemas in color, the Death of Casagemas again in blue and then “Evocation – The Burial of Casagemas”. In this latter canvas the compositional and stylistic influence of El Greco’s “The Burial of Count Orgaz” can be traced. Picasso began to use blue and green almost exclusively. “I began to paint in blue, when I realized that Casademas had died” Picasso later wrote. Restless and lonely, the arist moved constantly between Paris and Barcelona, depicting isolation, unhappiness, despair, misery of physical weakness, old age, and poverty; all of it in shades of blue. In the allegorical La Vie (1903), in monochrome blue, the man has the face of his deceased friend. In 1904 Picasso finally settled in Paris, at 13 Rue Ravignan, called “Bateau-Lavoir”. He met Fernande Olivier, a model, who would be his mistress for the next seven years. He even proposed to her, but she had to refuse because she was already married. They paid frequent visits to the Circus Médrano, whose bright pink tent at the foot of the Montmartre shone for miles and was quite close to his studio. There, Picasso got ideas for his pictures of circus actors. The pub Le Lapin Agile (The Agile Rabbit) was a meeting place of young artists and authors. In the pub, Picasso got acquainted with the poets Guillaume Apollinaire and Max Jacob. The landlord, Frédé, accepted pictures as payment, and this made his café attractive for the artists and he acquired a splendid collection of paintings, including, of course, one by Picasso “At the Lapin Agile”, with Picasso as a harlequin and Frédé as a guitar player. The picture “Woman with a Crow” shows Frédé’s daughter. By 1905, Picasso lightened his palette, relieving it with pink and rose, yellow-ochre and gray. His circus performers, harlequins and acrobats became more graceful, delicate and sensuous. In 1906 the art dealer Ambroise Vollard bought most of Picasso’s “Rose” pictures. This marked the beginning of Picasso's prosperity: he would never again experience financial worries. Accompanied by Fernande the painter traveled to Barcelona, then to Gosol in the north of Catalonia, where he painted “La Toilette”. Deeply impressed by the Iberian sculptures at the Louvre, he began to think over and experiment with geometrical forms.

Cubism: 1907-1917“Cubism is no different from any other school of painting. The same principles and the same elements are common to all. The fact that for a long time cubism has not been understood and that even today there are people who cannot see anything in it, means nothing. I do not read English, and an English book is a blank to me. This does not mean that the English language does not exist, and why should I blame anyone but myself if I cannot understand what I know nothing about?” - Picasso

|

|

|

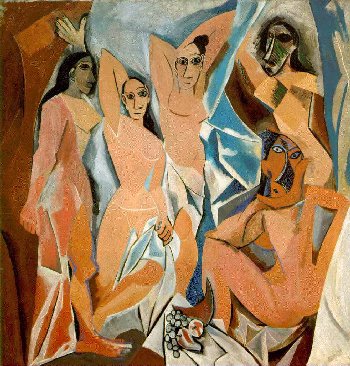

African PeriodIn 1907, after numerous studies and variations Picasso painted his first Cubist picture - “Les demoiselles d’Avignon”. Impressed with African sculptures at an ethnographic museum he tried to combine the angular structures of the “primitive art” and his new ideas about cubism. The critics immediately dubbed this stage in his work the African Period, seeing in it only an imitation of African ethnic art. “In the Demoiselles d’Avignon I painted a profile nose into a frontal view of a face. I had to depict it sideways so that I could give it a name, so that I could call it ‘nose’. And so they started talking about Negro art. Have you ever seen a single African sculpture -- just one -- where a face mask has a profile nose in it?” Picasso wrote. Picasso’s new experiments were received very differently by his friends, some of whom were sincerely disappointed, and even horrified, while others were interested. The art dealer Kahnweiler loved the Demoiselles and took it for sale. Picasso’s new friend, the artist Georges Braque (1882-1963), was so enthusiastic about Picasso’s new works that the two painters came together to explore the possibilities of cubism over several of the following years. In the summer of 1908, the two began their experiments by going on holidays in the countryside. Afterwards, they found that they had painted very similar pictures completely independently of each other.

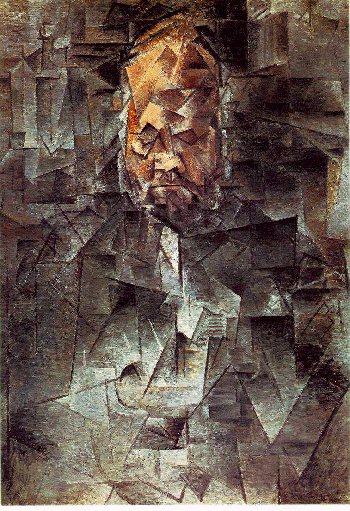

Analytical CubismBread and Fruit Dish on a Table (1909) marks the beginning of Picasso’s “Analytical” Cubism: he gives up a central perspective and splits forms up into facet-like stereo-metric shapes. The famous portraits of Fernande, Woman with Pears, and of the art dealers Vollard and Kahnweiller are fulfilled in the analytical cubist style . By 1911, Picasso’s relationship with Fernande went through a crisis. He broke up with her and started a liaison with Eva Gouel (Marcelle Humbert), whom he called “Ma Jolie”.

Synthetic or Collage CubismBy 1912 the possibilities of analytical cubism seemed to be exhausted. Picasso and Braque began new experiments. Within a year they were composing still lifes of cut-and-pasted scraps of material, with only a few lines added to complete the design, such as Still-Life with Chair Caning. These collages led to synthetic cubism -- paintings with large, schematic patterning, such as The Guitar. “Cubism has remained within the limits and limitations of painting, never pretending to go beyond. Drawing, design and color are understood and practiced in cubism in the spirit and manner that are understood and practiced in other schools. Our subjects might be different, because we have introduced into painting objects and forms that used to be ignored. We look at our surroundings with open eyes, and also open minds. We give each form and color its own significance, as we see it; in our subjects, we keep the joy of discovery, the pleasure of the unexpected; our subject itself must be a source of interest. But why tell you what we are doing when everybody can see it if they want to?” wrote Picasso. World War I (1914-18) changed the life, mood, state of mind, and, of course, art of Picasso. His fellow French artists, Braque and Derain, were called up into the army at the beginning of the war. The art dealer Kahnweiler, a German, had to go to Italy, and his gallery was confiscated. Picasso’s pictures became somber, showing realistic more often, for example Pierrot. “When I paint a bowl, I want to show you that it is round, of course. But the general rhythm of the picture, its composition framework, may compel me to show the round shape as a square. When you come to think of it, I am probably a painter without style. ‘Style’ is often something that ties the artist down and makes him look at things in one particular way, the same technique, the same formulas, year after year, sometimes for a whole lifetime. You recognize him immediately, for he is always in the same suit, or a suit of the same cut. There are, of course, great painters who have a certain style. However, I always thrash about rather wildly. I am a bit of a tramp. You can see me at this moment, but I have already changed, I am already somewhere else. I can never be tied down, and that is why I have no style,” Picasso wrote. In 1916, the young poet Jean Cocteau brought the Russian ballet impresario Diaghilev and the composer Erik Satie to meet Picasso in his studio. They asked him to design the décor for their ballet “Parade”, which was to be performed by Diaghilev's Ballet Russe. The meeting and Picasso’s affirmative answer would bring major changes to his life in the followng years. In 1917, he traveled to Rome with Cocteau and spent time with Diaghilev’s ballet company, working on décor for “Parade”. There, Picasso met Igor Stravinsky and fell in love with the dancer Olga Khokhlova. He accompanied the ballet group to Madrid and Barcelona because of Olga, and eventually persuaded her to stay with him.

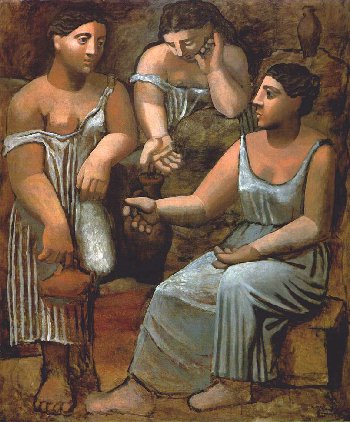

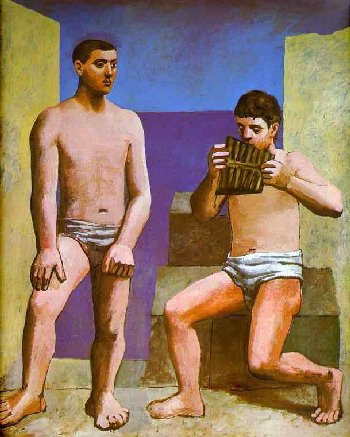

Between Wars, Classicism and Surrealism: 1918-1936In 1918, Olga and Picasso got married. The young couple moved to an apartment that occupied two floors at 23 Rue La Boétie, acquired servants, a chauffeur, and began to move in different social circles, no doubt due to Olga’s influence. The chaotic get-togethers Picasso had with his artist friends gradually changed into formal receptions. Picasso’s image of himself changed as well, and this was reflected in the more conventional style he adopted in his art and the way in which he consciously made use of artistic traditions and ceased to be provocative. After cubism, Picasso returned to more traditional patterns -- if not exactly classical ones -- and this period is thus known as his Classicist period. A typical example of this new style is The Lovers. From time to time, he would return to cubism. His collaboration with the Ballet Russe went on: he worked on décor for “Le Tricorne” and drew portraits of the dancers. In 1920, he began to work on the décor for Stravinsky’s ballet Pulcinella. With the birth of his son Paul (Paolo) (1921), he returned to the Mother and Child theme again and again: Mother and Child. In 1921, he painted his Cubist Three Musicians, in which he used a group of people as a cubist subject for the first time. The three figures are characters from the Italian Commedia dell’Arte (Pierrot, Harlequin and a monk). Though created after his Cubist period, the picture came to be regarded as a masterpiece of cubism. “Those who set out to explain a picture are setting out on the wrong foot. A short time ago Gertrude Stein elatedly informed me that at last she understood what my painting ‘Three Musicians’ represented. It was a still life!” wrote Picasso. In 1923, Picasso painted The Pipes of Pan, which is regarded as the most important work of his “classicist period”. Other interesting works include The Seated Harlequin and Women Running on the Beach. “Of all the misfortunes – hunger, misery, being misunderstood by the public – fame is by far the worst. This is how God chastises the artist. It is sad. It is true,” wrote Picasso God had chastised Picasso. By the mid-twenties he became so popular that he “had to suffer a public that was gradually suppressing his individuality by blindly applauding every single picture he produced.” In addition to this, the artist was having marital problems. His wife Olga, a former ballet dancer, for whom the attention and admiration of the public was necessary, vital, and natural, could not understand Picasso's discomfort with his fame. Picasso tried to preserve his independence by taking an interest in the unknown and the unfamiliar. He set up a sculptor’s studio near Paris and began to experiment with this new artistic medium. He produced a series of assemblies with a Guitar theme, using objects such as shirts, floor-rags, nails and string, as well as sculptures. In 1927, Picasso began an affair with seventeen-year old Marie-Thérèse Walter, his son Paolo's nurse. Much of his work after 1927 is fantastic and visionary in character. His Woman with Flower (1932) is a portrait of Marie-Thérèse, distorted and deformed in the manner of Surrealism. The Surrealism movement was growing in strength and popularity at the time, and even Picasso could not really avoid being influenced by this group of Parisian artists, although they, conversely, regarded him as their artistic stepfather. “I keep doing my best not to lose sight of nature. I want to aim at similarity, a profound similarity which is more real than reality, thus becoming surrealist,” Picasso wrote. The worst time of his life, according to Picasso himself, began in June 1935. Marie-Thérèse was pregnant with his child, and his divorce from Olga had to be postponed again and again: their common wealth had become a target for lawyers. During this time of personal financial crisis, Picasso would add the bull, either dying or snorting furiously and threatening both man and animal alike, to his artistic arsenal. Being Spanish, Picasso had always been fascinated by bullfights, the so-called “tauromachia”. On October 5th of that year, his second child, a daughter, Maria de la Concepcion, called Maya, was born. In 1936, he met Dora Maar, a Yugoslavian photographer. Later, during the war, she became his constant companion. See Portrait of Dora.

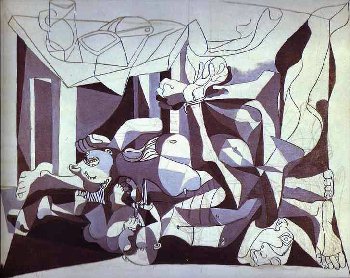

Wartime Experience: 1937-1945“Guernica, the oldest town of the Basque provinces and the center of their cultural traditions, was almost completely destroyed by the rebels in an air attack yesterday afternoon. The bombing of the undefended town far behind the front line took exactly three quarters of an hour. During this time and without interruption a group of German aircraft – Junker and Heinkel bombers as well as Heinkel fighters – dropped bombs weighing up to 500 kilogrammes on the town. At the same time low-flying fighter planes fired machine-guns at the inhabitants who had taken refuge in the fields. The whole of Guernica was in flames in a very short time.” - The Times, April 27, 1937. The Spanish government had asked Picasso to paint a mural for the Spanish pavilion at the Paris World Exhibition. He planned to depict the subject “a painter in his studio”, but when he heard about the events in Guernica, he changed his original plans. After numerous sketches and studies, Picasso gave his own personal view of the tragedy. His gigantic mural Guernica has remained part of the collective consciousness of the twentieth century, a forceful reminder of the event. Though painted for the Spanish government, it wasn't until 1981, after forty years of exile in New York, that the picture found its way to Spain. This was because Picasso had decreed that it should not become Spanish property until the end of fascism. In October 1937, Picasso also painted the “Weeping Woman” as a kind of postscript to “Guernica”. In 1940, when Paris was occupied by the Nazis, he handed out prints of his painting to German officers. When they asked asked him “Did you do this?” (referring to the pictures), he replied, “No, you did”. Whether those world-reknowned military brains were simply unable to perceive the symbolism of the picture, or whether it was Picasso's fame that stopped them from taking any action, the painter was not arrested and went on working. During the war, he met a young female painter, Françoise Gillot, who would later become his third official wife. With his Charnel House of 1945, Picasso concluded the series of pictures that he had started with “Guernica”. The connection between the paintings becomes immediately obvious when we consider the rigidly limited color scheme and the triangular composition of the center. However, in the latter painting, the nightmare had been superceded by reality. The Charnel House was painted under the impact of reports from the Nazi concentration camps which had been discovered and liberated. It wasn't until then, that people realized the atrociousness of the Second World War. It was a time when the lives of millions of people had been literally pushed aside, a turn of phase which Picasso expressed rather vividly in the pile of dead bodies in his Charnel House.

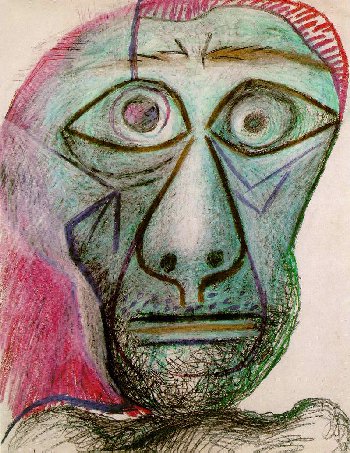

After WWII, The Late Works: 1946-1973In 1944, after the liberation of Paris, Picasso joined the Communist Party and became an active participant of the Peace Movement. In 1949, the Paris World Peace Conference adopted a dove created by Picasso as the official symbol of the various peace movements. The USSR awarded Picasso the International Stalin Peace Prize twice, once in 1950 and for the second time in 1961 (by this time, the award had been renamed the International Lenin Peace Prize, as a result of destalinization) . He protested against the American intervention in Korea and against the Soviet occupation of Hungary. In his public life, he always expressed humanitarian views. After WWII, Françoise gave birth to two children: Claude (1947) and Paloma (1949). Paloma is the Spanish word for “dove” -- the girl was named after the peace symbol. Picasso would not settle down, and more women would come into his life, some coming and going, like Sylvette David; and some staying longer, like Jacqueline Rogue. Picasso would remain sexually active and seeking throughout most of his life; it wasn't that he was looking for something better than what he had had previously; the artist had a passion for the new and untried, evident in his travels, his art and, of course, his women. For him, it was a way of staying young. In the summer of 1955, Picasso bought “La Californie”, a large villa near Cannes. From his studio, he had a view of the enormous garden, which he filled with his sculptures. The south and the Mediterranean were just right for his mentality; they reminded of Barcelona, his childhood and youth. There, he painted “Studio ‘La Californie’ at Cannes” (1956) and Jacqueline in the Studio (1956). By 1958, however "La Californie" had become a tourist attraction. There had been a constantly increasing stream of admirers and of people trying to catch a glimpse of the painter at his work, and Picasso, who disliked public attention, chose to move house. Picasso bought the Chateau Vauvenargues, near Aix-en-Provence, and this was reflected in his art with an increasing reduction of his range of colors to black, white and green. The mass media turned Picasso into a celebrity, and the public deprived him of privacy and wanted to know his every step, but his later art was given very little attention and was regarded as no more than the hobby of an aging genius who could do nothing but talk about himself in his pictures. Picasso’s late works are an expression of his final refusal to fit into categories. He did whatever he wanted in art and did not arouse a word of criticism. With his adaptation of “Las Meninas” by Velászquez and his experiments with Manet’s Luncheon on the Grass, was Picasso still trying to discover something new, or was he just laughing at the public, its stupidity and its inability to see the obvious. A number of elements had become characteristic in his art of this period: Picasso’s use of simplified imagery, the way he let the unpainted canvas shine through, his emphatic use of lines, and the vagueness of the subject. In 1956, the artist would comment, referring to some schoolchildren: “When I was as old as these children, I could draw like Raphael, but it took me a lifetime to learn to draw like them.” In the last years of his life, painting became an obsession with Picasso, and he would date each picture with absolute precision, thus creating a vast amount of similar paintings -- as if attempting to crystallize individual moments of time, but knowing that, in the end, everything would be in vain. Pablo Picasso passed away at last on April 8, 1973, at the age of 92. He was buried on the grounds of his Chateau Vauvenargues. “The different styles I have been using in my art must not be seen as an evolution, or as steps towards an unknown ideal of painting. Everything I have ever made was made for the present and with the hope that it would always remain in the present. I have never had time for the idea of searching. Whenever I wanted to express something, I did so without thinking of the past or the future. I have never made radically different experiments. Whenever I wanted to say something, I said it the way I believed I should. Different themes inevitably require different methods of expression. This does not imply either evolution or progress; it is a matter of following the idea one wants to express and the way in which one wants to express it.” - Picasso

Picasso's Greatest Artworks:

| ||