1. CONFLICTING OPINIONS

For a painter/sculptor who is still largely unrecognised outside his native Belgium, Antoine Joseph Wiertz (1806-1865; Self Portrait) certainly divides opinion. The art dictionaries and encylopedias that bother to mention him in their brief entries variously describe his work as banal, melodramatic, morbid, mystical, ambitious. Opinions about the artist himself are equally conflicting, ranging from visionary, eccentric, to meglomaniacal. If there is any agreement about Wiertz and his oeuvre, it is that his single-mindedness and considerable self-confidence produced some utterly distinctive paintings on unusual subjects that are not much like anybody else's. Astonishing, then, that so few books have been written about Wiertz, and what has is now many decades out of print. Moreover, to my knowledge, there has never been a Wiertz monograph written in English. In other words, he is long overdue substantial critical attention. I hope this short essay will introduce some of Wiertz's work to those who have not yet encountered this most idiosyncratic of artists.

Wiertz was born in Dinant on 22 February 1806. Showing early promise, he studied at the Academy of Art in Antwerp under Herreybs and Van Brée, and later in Rome where he achieved second prize in the prestigious Prix de Rome, a competition he would eventually win in 1830. During the late 1820s he visited Paris, studying the work of his idol, Rubens, in the Louvre, while earning enough to feed himself by painting quick portraits. He later said that he painted the portraits for bread and the religious and historical subjects for honour. Often on a huge scale, his canvases range from traditional religious scenes to the erotic, grotesque and disturbing visions depicted in his most arresting work. After his death, his Brussels studio became the Wiertz Museum.

Tête de mort

2. MAGICAL EROTICISM

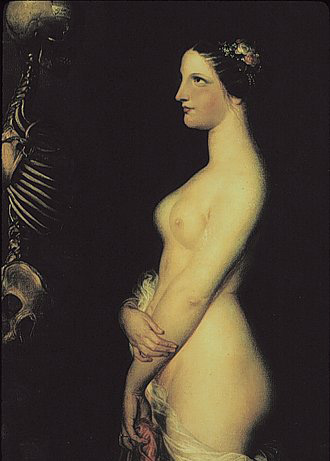

My first encounter with Wiertz's work was, appropriately, on the front cover of Dedalus' 1992 edition of J-K Huysmans' novel La Bas - a heady fin de siècle brew of religion and sexual magic, with an intermittent discourse on the trial of notorious 15th century sadist and child-murderer Gilles de Rais. The work chosen to lead one into this shadowy world is The Young Witch (aka The Young Sorceress; La jeune Sorcière) of 1857. Wiertz's painting is suitably charged with a combination of innocence, overt sexuality, grotesquerie, and supernatural danger. Those lecherous faces in the top left corner remind us that we too are voyeurs of this curious scene, lit by the voluptuous fleshtones of Wiertz's nubile temptress, who is provocatively 'penetrated' by that thrusting, phallic broomstick. The tension arising from the artist's cunning juxtaposition of painterly classicism and somewhat crude titillation invests the work with a striking, magical eroticism. Speaking of the latter, brings us to Aubrey Beardsley, the quintessential English decadent artist/writer of the fin de siècle. It seems that Wiertz's distinctive oeuvre had not escaped his attention. A footnote in the unexpuragated version of Beardsley's unfinished novel The Story Of Venus And Tannhäuser (the censored version was titled Under The Hill) refers to the English artist JMW Turner as "the Wiertz of landscape-painting" (see p.58 of the 1995 Wordsworth Classic Erotica edition). Quite what one is to make of this unelaborated comparison is unclear, since at the time it was written (during the 1890s) Turner's radical experiments in landscape colour were not universally appreciated. At best, one imagines that Beardsley was drawing attention to both artists' capacity to produce startlingly dramatic and energetic effects in their respective fields of interest. As events have turned out, it appears particularly ironic that Turner, now the internationally renowned artist, should be described in terms of Wiertz who nowadays (and doubtless then, also) is merely regarded as an eccentric minor player in the History of Art.

The Young Witch

3. EXTREME STATES OF CONSCIOUSNESS

A second encounter with Wiertz's work came via another book cover - the 1978 Penguin Classics edition of Lautréamont's Maldoror and Poems. This time the painting was The Premature Burial (aka Buried Alive; Inhumation précipitée) of 1854. Art commentator, Jeffery Howe, suggests that Wiertz was inspired by Edgar Allan Poe, in whose fiction premature burial is a recurring theme (e.g. the short story entitled The Premature Burial, Madeleine in The Fall Of The House Of Usher, and Fortunato in The Cask Of Amontillado). Poe had been dead five years by the time this painting appeared, though doubtless would have approved of its memorable evocation of a fervid, nightmarish scene. In fact, the work of Wiertz, Poe and Lautréamont - all three working around the same time - displays a common obsession with extreme states of consciousness, manifest in romanticised imagery of menacing, grotesque, violent, erotic and tragic proportions. Hunger, Madness, Crime (Faim, Folie, Crime, 1853) is another painting in this vein; the grotesque detail of a child's leg in a cooking pot is visible at the right edge of the canvas.

La Faim, la folie et le crime

Wiertz's audacious 1853 triptych, Last Thoughts And Visions Of A Decapitated Head (Pensées et Visions d'une tête coupée) incorporates most of these elements with a terrifying force and sense of movement, whereas the bizarre stillness of a related work, Guillotined Head (1855), arouses feelings of pity and revulsion in about equal measure. The phantasmagoric aspects of Wiertz's paintings - likewise, the phantasmagoric aspects of Poe's and Lautréamont's fiction - attracted the attention of the surrealists, leading the occasional commentator to subsequently describe the artist as pre-surrealist. However, while Lautréamont was practically discovered and then adored by the surrealists, thus guaranteeing his preeminence among surrealist writers, Wiertz's legacy was left to languish in obscurity.

La Belle Rosine

4. THE CINEMATIC ELEMENT

I've already referred to that startling sense of movement and energy present in some of Wiertz's finest paintings, and because of this I now wish to describe what to my mind amounts to a 'cinematic element' in his work. Of course, Wiertz had been dead and buried about 30 years before the Lumière brothers first publicly projected their films in Paris, 1895; so I'm not claiming that he foresaw the advent of the motion picture. Nevertheless, some of his paintings are so concerned with conveying movement and energy, as opposed to 'frozen time', that he is certainly pushing at the limits of a static medium. Nowhere is this cinematic element more vividly evident than in the aforementioned triptych Last Thoughts And Visions Of A Decapitated Head. Here, Wiertz depicts an execution by guillotine in three panels. The first suggests a low-angle view of the headless body, our gaze guided upwards by the pointing finger of a spectator in the foreground; the second presents a high-angle view as our now downward gaze is divided between the falling body and the decapitated head which, resting in the bottom right corner of the frame, leads us into the third panel. At this point, Wiertz 'jump cuts' dramatically from a spectator's view of events to a 'subjective shot' of the "last thoughts and visions of a decapitated head", presenting us with an extraordinary, expressionistic sensory whorl where objects and people become indistinct. And so the staccato movement across the three panels operates likes a sequence of filmic montage, bursting with the sort of rhythmic and psychological energy that film directors like Abel Gance and Sergei Eisenstein would unleash upon the audiences of their experimental silent epics of the 1920s. If Wiertz doesn't exactly predict the advent of motion pictures, he does at least anticipate the basic techniques of film editing and deploys them to stunning effect.

Cinematic tendencies are also at play in a two-part work entitled Old Nick's Mirror I (Le Miroir du Diable I) and Old Nick's Mirror II (Le Miroir du Diable II), both from 1856. In the first painting we see a well-to-do beauty admiring her elegant clothes and necklace in a mirror. Yet, when we come to the second painting, a major transformation has taken place. Now we are confronted by an unashamedly erotic image, intensified by the introduction of a voyeuristic male behind the mirror who, judging by his horns, is probably one of the devil's emissaries, if not Old Nick himself. In cinematic terms a dissolve would achieve this kind of dream-like transition, and Wiertz seems to be asking us to imagine a similar perceptual movement in a static medium by carrying over the pose and facial expression to the second painting, only to radically alter the context of these gestures by an unexpected striptease (one is reminded of how Buñuel and Dali use dream-like dissolves during the breast-fondling sequence of Un Chien Andalou). The back of the hand placed on the hip and that sensuously painted, jutting elbow now appear knowingly coquettish. In a trick of the light almost, our innocent, fashionable beauty is exposed as a provocative, vain temptress, reminiscent of the young woman in The Young Witch. Yet, like a sequence of filmic montage, the meaning(s) resides not in the content of either of the two paintings in isolation, but in their juxtapostion. Once again Wiertz's handling of supernatural and erotic material is captivating.

Nudity is given an explosive context in The Outrage Of A Belgian Woman (aka A Blow From The Hand Of A Belgian Lady; Le Soufflet d'une dame belge) of (1861). If in The Suicide (Le Suicide) of 1854 we are spared the actual effects of gunfire as the suicide's features are engulfed by a cloud of gunsmoke, in The Outrage Of A Belgian Woman the depiction of violence is more explicit, and still seems rather shocking, even by today's standards. A chubby, Rubensesque female fends off a military assailant by firing a pistol into his face, thus escaping probable rape. Wiertz superbly captures the panic and hysteria of the incident by dividing our gaze between three points of tension in the composition. Firstly, the large, powerful hand and forearm of the assailant around the woman's waist, signifying entrapment and the threat of sexual violation, is given a foreground emphasis. Secondly, as our gaze darts upwards across the woman's bare chest we see the pistol, held at a parallel angle to the assailant's forearm. The angle of the pistol serves both to underline (and thus partly frame) the woman's anguished cry, which is the central point of tension within the composition, and then to direct our gaze along its barrel to the third point of tension - the exploding face of the assailant. A close-up of this section of the canvas shows that Wiertz was keen to depict the full force of the gunfire in all its gory details; consequently, this image wouldn't be out of place in contemporary cinema. One could imagine a film director approaching the whole incident by cutting rapidly between these points of tension, in the order I've suggested, to gain maximum dramatic effect. Of course, the painter of a single frame painting - forever stuck with the master shot - has no such control of our perceptual ordering of events. Nevertheless, by skilful arrangement of visual cues Wiertz suggests a perceptual route through the painting which encourages us to make close-ups of and therefore cuts between the various points of dramatic tension. Techniques like this, allied to striking images, mean that Wiertz's still undervalued work has the capacity to fire the imagination of contemporary viewers.

|

|