| Charles Prendergast - Canadian Post-Impressionist

1863-1948, St John's Newfoundland. Lived most of his life in Boston, MA. Charles Prendergast's career as a painter does not start with himself. It starts with his older brother Maurice (October 10, 1858 - February 1, 1924) who apprenticed to a commercial artist. Maurice was not a very good painter. He basically copied whatever his mentor showed him. In 1893 he travelled to Paris to study painting there and returned in 1895 not much improved. Maurice was influenced by the Impressionists, but colour-wise his paintings remained drab, muddy-looking and he used too many pastels. Meanwhile Charles Prendergast he become a painter and successful framer/furniture maker. He adopted some of his older brothers impressionist techniques, but kept a much more loose and flamboyant style, frequently using gold paint to liven up the canvas. Both brothers tended to paint leisure activities. Maurice tended to paint women with parisols or civic areas whereas Charles was more sportsy, painting scenes of beaches, polo-players and circuses. After Maurice died in 1924, Charles began painting more often and his fame and skill eclipsed that of his brother. In 1925 Charles traveled to France and married Eugénie van Kemmel upon their return to America. They lived in Westport, Connecticut until his death in 1948.

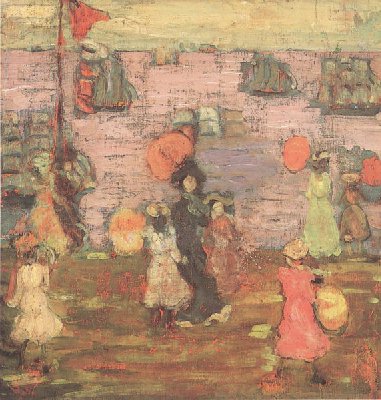

Telegraph Hill, 1900 - Maurice Prendergast

Two Hunters on Horseback and Deer in Landscape, c. 1912–15 - Charles Prendergast The Dance, 1916 - Charles Prendergast

Angels, c. 1916-18 - Charles Prendergast Fairy Story, c. 1922 - Charles Prendergast Three Part Screen, 1929 - Charles Prendergast Holiday Beach Scene, c. 1931-1932 - Charles Prendergast Bathers Under the Tree, 1940 - Charles Prendergast

|

|

|

Charles Prendergast: Beauties...of a Quiet Kind

By Nancy Mowll Mathews Charles Prendergast (1863-1948), younger brother of the Canadian-American modernist/post-impressionist painter Maurice Prendergast (1858-1924), produced just over one hundred finished pictorial works. Based as they were on ancient motifs and contemporary folk art subjects, these painted and carved objects have so few parallels in the art of Prendergast's time that they stand outside the established history of American art and have earned their creator a small, but very passionate, following among connoisseurs and art historians. His works will probably always be the province of the very few because, by their very nature, they are fragile and precious, beautiful to look at and elusive in meaning. But when examined carefully, they reveal a rich world of wit and symbol that is unexpectedly universal in its appeal. Prendergast's works are exceptional also because they constitute a second career for the artist who first rose to prominence as a craftsman and framemaker. It is more common for the the artist to begin his career as a painter and then later turn to the decorative arts, as did Louis Comfort Tiffany and John LaFarge. But Charles Prendergast established himself as a premier American framemaker by the age of forty-five and then began his career as a fine artist (painter and sculptor) when he was in his fifties. Baptized Charles James Prendergast in the Roman Catholic Basilica of John the Baptist in St. Johns, Newfoundland, the artist was the youngest of six children born to Maurice and Malvina Germaine Prendergast. The family was solidly middle or uppermiddle class; his father was the owner of a general store and his mother the daughter of a Boston physician. Of Charles' five brothers and sisters, only the two eldest, Maurice and his twin sister Lucy, survived childhood, and only Maurice survived with Charles into adulthood. The family business failed, and the Prendergasts moved to Boston when Charles was four years old. Both Charles and Maurice had developed refined tastes as children, were known to be facile with drawing pencils, and gravitated to artistic circles when they left school. Maurice found his way into a commercial art firm and by age twenty-one was a professional designer. Charles, by his own admission, was less directed than Maurice. He became an errand boy for the art gallery Doll & Richards when he was in his teens, but he left to make two voyages to England as a deck-hand on a cattle boat. When he returned to Boston in 1887 he recalled working for another (unnamed) art gallery and was listed for the first time in the Boston City Directory as "clerk." In 1890 he shipped out again, this time to Paris with Maurice where the brothers began taking art classes. Maurice, although now in his thirties, applied himself to the art student regimen, studying at the well-known academies of Colarossi and Julian. Charles, a handsome young man in his late twenties, was less dedicated to his studies and soon returned to Boston. Charles may have been discouraged from pursuing a fine arts career after seeing the high level of work produced in the classes in Paris and seeing his brother's career quickly take off in that competitive atmosphere. Unlike Maurice, he had not developed his early talent in drawing by working in the commercial arts, and instead had gained more experience in the business side of the fine arts. By 1892 Charles had become a partner in a firm that produced decorative wooden moldings, especially for fireplace mantels. He may have joined the firm as a salesman, since his experience lay in that field, but by the time his brother returned from Paris in 1894, Charles had gravitated toward the manufacturing side, gaining experience in all aspects of the carving of decorative wood objects. The change in Maurice's life after four years in Paris inevitably caused a change in his brother's life as well. Maurice moved back into the family home, which now consisted only of Charles and their father (their mother died in 1883). Maurice had entered the world of high art -- his pictures were now on view at Charles' former employer, Doll & Richards -- and his friends were the artists whose work Charles had handled and sold. In comparison, Charles' woodwork business seemed unbearably mundane and, as he told his biographer, he slipped into a depression: ''I was so damn miserable, so damn unhappy, so damn aggravated, that I plain got sick of having myself around."[l] Maurice and his painter friends ultimately suggested a solution to Charles' dilemma. They needed frames, particularly frames made by someone "artistic;" someone who understood the effect they were trying to achieve in their paintings and who had the skill and the creativity to carve a frame that would enhance that effect. Maurice's new artist-friends, such as Hermann Dudley Murphy and Sarah Choate Sears, were also independently wealthy and could afford handmade frames for their own works and the works of the other artists they collected. The art world in Boston, with its aristocratic make-up and its emphasis on refined taste, was perfect for an artist-framemaker. As Prendergast put it, ''Wood-carving is a beautiful art, and it requires a refined taste to appreciate it. Its beauties are all of a quiet kind."[2] In 1911 Charles Prendergast decided to spend the summer in Italy. It had been years since he traveled abroad and the trip signaled a new financial and professional security. Since Charles went without Maurice (who would join him at the end of the summer), he was not merely tagging along on one of his brother's painting trips. From Charles' earliest surviving sketchbook ("Sketchbook D," CR 2409, Museum of Fine Arts, Boston) we might postulate that he planned the sojourn as a springboard into the pictorial arts. This hypothesis is supported by the fact that Charles' frames at about this time broke new ground in their use of color (blue, gold, and rose) and of high relief rosettes, birds, and angels' heads. This experimentation with color and naturalistic form in his frames brought him to the threshold of a new medium: the carved pictorial panel. Italy was a revelation to him; he loved the sensation of stepping into the past. He studied the frames and woodcarving he found in antique shops and those made by local craftsmen, bringing several of them home. He bought photographs of Italian art, architecture, and design to add to the brothers' study collection. And after he returned he began his first panel, Rising Sun, as if to capture the antique spirit so vividly conveyed in the rich Italian artistic tradition. For years afterward, he experimented with overtly Christian subjects, including angels, Madonnas, and other biblical images. While he drew his motifs from a variety of sources once he returned to the United States, his use of the gilded pictorial panel, which allows the viewer a glimpse of an exotic, timeless world, were drawn directly from the churches and museums he had seen in Italy. Beyond the general notion that Charles Prendergast's 1911 trip to Italy was seminal, very little else is known about the origins, sources, and intentions of these new pictorial panels. He began producing them slowly, at the rate of three or four a year, dividing his days between work on the panels and his frame commissions. The first panels were created in Boston in the large studio he shared with Maurice at 56 Mount Vernon Street. It is not known whether he tried to exhibit them in Boston, or if he considered them more than just a casual departure from his professional frame work. Soon after he and Maurice moved to New York in late 1914, he was engaged to show two of his panels in a group exhibition of paintings, drawings, and sculpture at the Montross Gallery. This led to an increasingly active schedule of exhibiting, selling, and participating in artists' associations. As if to signal his new identity, the American Art Annual's 1915 "Who's Who in Art" lists Charles Prendergast as a painter. In his first few panels such as Rising Sun, Prendergast attempted a sculpted relief effect that ties his panels to the tradition. of relief sculpture and also suggests a parallel with contemporary works by Paul Gauguin and Raymond Duchamp-Villon. But Charles soon abandoned the high relief of Rising Sun for the use of incised lines, suggesting low relief, as in Egyptian or Mesopotamian mural reliefs. The lower relief and incised panels also relate to sources in two-dimensional media, such as the one source Prendergast himself acknowledged: Chinese and Persian miniatures. Prendergast remembered studying them in the Museum of Fine Arts when he lived in Boston, and was struck by the effect of miniaturization and colorful simplification. The artist indulged his own childlike response to them in recalling the long-ago pleasure: "My, my!...I thought it was wonderful those little animals, those little trees, those little houses, all painted so slick and fine. I couldn't get over them."[3] Prendergast's sources, in ancient, Oriental, primitive, and medieval art, were not unusual among the artists in the Prendergast circle in New York at that time. While there were no other carved panels in Charles' first exhibition, there were works that drew on some of the same sources. Maurice Sterne, for instance, had just returned to New York after traveling to Egypt, India, Burma, and Bali where he spent two years. In the spirit of Gauguin, Sterne painted large compositions of nude Balinese women in various contemplative poses. Not surprisingly, the artist closest in style and subject matter to Charles Prendergast was his brother, although that was not always obvious from the works displayed side by side in exhibitions from 1915 onward; in fact Maurice and Charles probably chose works for public exhibition that would stress their differences. However, their studio made clear the many similarities in their work and their shared interest in many of the same ideas and motifs. From 1912 until 1915, they both explored the world of the antique and exotic, the childlike and the primitive. They drew on myriad sources, gleaned from visits to museums and galleries, as well as their avid reading of art books and periodicals. They both drew on these sources to evoke an idyllic world, a golden age that gave pleasure and solace to an audience increasingly burdened with the exigencies of modern life and the approaching world war. Charles Prendergast, in particular, was drawn to subjects that symbolized fruitfulness, renewal, and rebirth, as in Rising Sun and Annunciation (Williams College Museum of Art). One might speculate that his interest in these themes arose not only from the deteriorating world situation, but also from his own joy in his second career. To be reborn as a figural artist and painter, at the time many of his friends were facing retirement, was a blessing for which he never stopped being grateful. In 1921, after Charles had been producing panels for almost ten years, the brothers were asked to provide the inaugural exhibition for a new gallery in New York, established by the Frenchman Joseph Brummer. Brummer shared the Prendergasts' interest in mixing modernist and antique art, and he installed their works in a second-floor gallery above an exhibit of Greek, Egyptian, and Gothic pieces. The juxtaposition of old and new worked very well for the Prendergasts, particularly for Charles, whose eight panels were universally admired by critics. Three years later, Maurice Prendergast died, leaving Charles alone in their New York studio and apartment at 50 Washington Square South. After Maurice's death, Charles' standing in the New York art world seemed to increase rather than decrease. This was partly because he was now the keeper of Maurice's flame, and the numerous. memorial exhibitions and tributes to Maurice in the next ten years required his generous participation. He began to associate not only with artists and dealers, but also with museum directors, curators, and art history writers. As in the past, Maurice's reputation opened doors for him, but Charles established himself on his own. For instance, the Kraushaar Gallery mounted the first memorial exhibition of Maurice's work in 1925, and then became the principal dealer for Charles. The Whitney Museum of American Art held a major retrospective of Maurice Prendergast in 1934, and its director, Juliana Force, became a close friend. Charles also drew closer to Lillie Bliss, an early collector of Maurice's work who then became devoted to Charles' work. He also came into the orbit of Abby Aldrich Rockefeller who not only bought Maurice's paintings for the Museum of Modern Art, but also collected and commissioned works from Charles. Albert Barnes, who had competed with John Quinn for Maurice's paintings, later became a close friend of Charles and a major collector of his work over the years. From the time of Maurice's death until about 1932, Charles' art followed a number of disparate directions. One was the familiar route of the fantasy panels that he had begun in the teens (Fairy Story, Donkey Rider, and Bathers Under the Trees). Another was the revival of his interest in the decorative arts, particularly in making carved and painted chests and small boxes that evoked both Italian Renaissance cassone and American folk crafts (Box). He also created a number of painted and gilded pictorial compositions on glass such as Decoration on Glass. Finally, he painted a series of watercolors of the hill towns along the southern coast of France during two trips he made with his new wife, Eugenie, in 1927 and 1929. The hill towns, as seen in watercolors and panels such as Holiday Beach Scene, were not only a new subject for Prendergast, but also signaled a new phase in his art. Critics no longer praised his skill in the evocation of antique or medieval art, instead they spoke of him as if he were an antique or medieval artist. As Suzanne Lafollette, author of Art in America, put it "a true primitive."[4] Prendergast's earlier panels, with their rich allusions to the art of other cultures, were obviously the product of a learned and clever craftsman. His work, from the late 1920s onward, reduced the number of art historical allusions and stressed instead the artist's own "naive" vision. The distortion of anatomy and natural forms, the flattening of perspective, and the use of simplified outlines could no longer be attributed to a study of this or that exotic art form, but seemed to be the creation of the artist himself. Later, in the thirties, Prendergast would marry this approach to scenes of everyday American life and become an identifiable American folk artist, but in the late twenties and early thirties he applied the style to a number of subjects in what he described as his "transition" period. Prendergast's new naive or primitive style paralleled the growth of interest among artists and collectors in American folk art at this time. Interest turned to passion for such collectors as Juliana Force and Abby Aldrich Rockefeller, who would later found her own museum of American folk art in Williamsburg, Virginia. In the 1930s, Charles Prendergast found a secure niche in the New York art world; and in 1935, at the age of seventy-two, he was given his first one-person exhibition. This exhibition came on the heels of the major retrospective showing of Maurice's work at the Whitney Museum of American Art in 1934. No doubt the renewed appreciation of his brother, ten years after his death, brought new attention to Charles as well. When the Kraushaar Gallery arranged an exhibition of his work, Charles took the opportunity to show the range of pieces he had created over the years. He included such works from the teens as The Riders and brought the viewer up to-date with his most recent works such as Holiday Beach Scene. He also included at least two paintings on glass and one painted screen to represent his continuing interest in decorative arts. The exhibition was well received and led to later exhibitions at Kraushaar in 1937 and 1941, as well as a joint exhibition with Maurice's work at the Addison Gallery of American Art in 1938. Charles no longer held a place in New York avant-garde circles, nor could he be called "famous" -- even to the degree that his good friend William Glackens continued to be -- but he was well-respected by the artistic community. Furthermore, he was dearly loved by the educated and refined audience of magazines such as The New Yorker, in which Lewis Mumford rhapsodized that "each of these pictures is a fresh glimpse of Heaven." [5] After the 1935 exhibition at Kraushaar, Prendergast increasingly concentrated on the American scene, particularly parks, country fairs, horse and boat races, and special days in small-town life. Now, when he painted animals, as in Circus and Polo Players, he placed them in familiar settings like circuses, zoos, or local parks, rather than in exotic forests or prancing in front of medieval castles. He joined the growing ranks of the so-called American folk artists of the 1930s, including Grandma Moses, Florine Stettheimer, and Horace Pippin. This naive style was encouraged and supported by high art collectors and museums, particularly the Whitney. American folk artists of this period were generally thought of as having had no academic training, a criterion that Charles technically met. But like many others, Prendergast brought his considerable knowledge and experience to a style that only appears to be naive, lifting the simple technique to a higher, more sophisticated level of expression. In the early months of 1946, after a period of ill health, Charles and Eugenie took a winter vacation in Florida, where he rejoined old artist-friends and was once more inspired to work. Driving around Winter Park and the small towns nearby, he zealously took to his sketchbook to record local scenes. The result was a series of eighteen watercolor sketches that he painted at that time, and four gesso panels that he executed when he returned to his studio in Westport, Connecticut, and on a subsequent trip to Florida the following winter. This group of works, including Florida Grove, continued his folk-art style of the later 1930s, but was strongly influenced by Haitian folk art. Prendergast borrowed the Haitian artists' strong coloring and active gestures to paint the African-American workers in the orange groves of central Florida. He felt that these workers were of more artistic interest than the whites: ''The men dress in such a manly way-in real, pure colors. And what material for a sculptor, especially their faces, men and women both! The colors of the women's clothes are wonderful. I got all excited over those Negroes. I even got excited by their roosters."[6] After exhibiting the Florida art series at another one-person exhibition at Kraushaar in the spring of 1947, Prendergast's health declined to the extent that he was no longer able to work. he died on August 20, 1948, at the age of eighty-five. Although Charles never achieved the standing among American artists that his brother enjoyed, he had the good fortune to have attained success in two careers. And, to have begun his work as a pictorial artist at the age one is now considered a senior citizen, and to have maintained it for over thirty-five years, was an extraordinary accomplishment. Furthermore, he had the rare pleasure of receiving major tributes in the form of exhibitions and glowing publications until his very last years. He did not live to see his work go out of style, because he had long ago bowed out of stylish, avant-garde circles and was content to address his work to a small circle of educated laymen. To a large extent, his reputation has been preserved by subsequent generations of this circle. But, with the increasing fragility of his aging gesso panels, frequent exhibitions (as he had in the last years of his life) have become impossible, and his admirers have therefore become an even smaller elite. Charles Prendergast was an artist who chose his directions carefully, so that his own skills and interests would be used to best advantage. As the brother of Maurice Prendergast, he had a guaranteed audience among the most influential dealers, collectors, and museum directors, and so he could afford to be quiet when other artists resorted to being loud. In the end, he used his talent and his circumstances well; he produced an art that exerts an undeniable charm, that is unusually original, and that has the power to last through the generations, celebrating as it does the cycle of rebirth and renewal. Notes: About the Author: Nancy Mowll Mathews is Eugenie Prendergast Senior Curator of 19th and 20th Century Art and Lecturer in Art at Williams College Museum of Art

|

|