|

||||

|

Gothicism and Romanticism in William Blake

By Michael Sloan The gothic style influenced both the art and the literature of the Romantic Period by presenting experience in a light of hard and depressing work. This shows the strongest through the poet and painter, William Blake, in such articles and paintings as “Songs of Innocence: the Chimney Sweeper”, “The Clod and the Pebble”, and through the paintings and writings in his “Books of Urizen.” If anything, William Blake used the ideas of Death and God, along with several thoughts on the failures of love and imagination in today’s society, and he wrote them through the Gothic style of darkness and bitter despair that is usually born of contempt for people or society itself. In Blake’s time he published several articles about to contrary ideas: innocence and experience. Both times he called them either the song of innocence or the songs of experience and both times he used the Gothic style to shove his point into the minds of the readers. In the songs of innocence he has a poem called The Chimney Sweeper. This poem was written as Blake’s response to the hardships that children of his time were forced to go through as chimney sweepers. These children would constantly be shoved up into a chimney and would be threatened with death on an hourly basis from both toxic chemicals and simply suffocation. In his articles he writes, “So your chimneys I sweep, and in soot I sleep./ There's little Tom Dacre, who cried when his head,/ That curled like a lamb's back, was shaved” (lines 4-6.) This quote has two tones to it, showing both the dark, Gothic side of experience, and the child-like side of innocence through the use of certain words. In line four Blake gives the reader a sense of darkness to every moment of the child’s life. Even in rest the child is constantly in a state of misery and despair due to the fact that the child sleeps in the filth of others just because its what he does. In lines five and six, however, Blake goes so far to say that experience is slowly mauling these children. He describes the child’s hair like a lamb’s back, giving the child a type of Biblical innocence just by using the word “lamb.” In line six Blake describes the loss of experience in a Gothic manner: through the transformation of something beautiful into the grotesque form of a shaved head. Blake even allowed the bleakness of resisting to sink in farther by saying later on that even if the head was not shaved that the child’s hair would be ruined. The idea that Blake would allow the fall from pure innocence into the tainted experience is not new to his readers. Several of Blake’s readers and opinionist find that Blake’s odd views on sexuality easily show the experience born in the division between man and a higher power when man refuses to accept his sexual freedom. One of several critics states, “A central component of Blake's mythology is his "idea of humanity as originally and ultimately androgynous" in which he "depicts a fallen state in which sexual division, lapse of unity between male and female as one being, is the prototype of division within the self, between self and other, and between humanity and God” (Thunder of Thought.) One of the key points in Gothicism is the idea that something is either extremely grotesque to the point of being an ugly mar on the “perfect society” or that the idea is so widely unaccepted that it is proclaimed as a sin against either humanity or the church. This quote explains that Blake’s philosophy on sex to be a prime example of what separates man and God: the fallen state of man. The irony is that his philosophy was so “bad” in his day that one would call him a sexual rebel, or someone who thought the classic way of doing things is a sin against God and his attempts to unite Himself with man. The mere basis of this belief puts Blake into the category of men that were influenced by Gothicism since society was developing its “prudence” and his ideas on sex obviously were commented on with a cringe or a look of disgust. Of course Blake’s idea of contraries seems to show itself through in every piece, this one being no exception. Using the dark Gothic style surrounding death, Blake went further on in the article to describe his views of what happens to an innocent child when they die. Blake writes, “Were all of them locked up in coffins of black./ And by came an angel who had a bright key,/ And he opened the coffins and set them all free” (lines 12-14.) The mere fact that black is describing the purgatory before the ascension to heaven shows that the afterlife is not the red carpet walk that the times would love to think it is. Instead purgatory is a small confined place of darkness and death that frightens most people to think about, and this, in itself, is a key idea on how to use the Gothic style to create a setting that chills the average person to think about being in. Of course, in the Gothic style the darkness and tainted never prevail forever. Somewhere along the lines a small ray of light has to peek through and resemble the hope of humanity in either the perseverance of the good or the extinction of the evil. Some analyzers of Blake’s works seem to think so as well: “This poem shows that the children have a very positive outlook on life. They make the best of their lives and do not fear death.” (William Blake Page.) This anonymous critic supports the idea that somewhere along the line Blake decided to give a small glimmer of hope for the innocent children, since they apparently never give up so the will earn their way into heaven. This is another element of the Gothic style, and in fact a very poplar theme for the writers, where the innocent little child is the only character with any real grip on what is right and what is wrong due to the nature of the “experienced adult.” The experience of life and death and all the hardships in between is not the only area William Blake seems to enjoy flinging the Gothic style: he also has a knack for applying the style to love and how it either works with the unison of man and God or fail with the greed of self satisfaction that man, males generally, is so well known for. This shows strongest in Blake’s poem “The Clod and the Pebble.” This work of his shows the back and forth argument between a very optimistic piece of road dirt or cow droppings and a very pessimistic outlook of a smooth river pebble. The Gothic style also uses personification to create critics of man out of everyday, ordinary and unnoticed items, as in a rock or a leaf. Blake writes, “But for another gives its ease,/ And builds a heaven in hell's despair." (lines 3 & 4.) This very optimistic piece of cow droppings seems to think that the love of mankind is the saving grace of man from its own hell Blake’s hell was the day he lived in and he openly enjoyed saying just that with his articles even though he had a good idea that most people would not look at it that way. When he found a new home he felt the same as the clod: full of optimism that this place would not be the same socially as the last. This is shown in a critic’s comments as she says, “Delighted by the natural beauty around him, Blake embarked on his new life in Sussex with great optimism” (The Gothic Life of William Blake.) Blake’s escape was through nature and this is where he drew his optimism from when he moved to Sussex. Of course this did not last long until he wrote the contrary argument to the poem. Blake writes, “Joys in another's loss of ease,/ And builds a hell in heaven's despite.” (lines 11 & 12.) These two lines are the contrary argument to the heaven that man makes in hell. When man is also blissfully happy in a relationship, or in heaven, he finds some kind of way to ruin it and creates his hell, even thought the person he wronged could still be there. This uses the Gothic format of heaven and hell to describe the futility of heaven. One way or another, man will shoot himself in the foot. This became evident in Blake’s own recorded life. The same female critic from before explains, “Blake was tired of the endless stream of trivial commissions from Hayley and his society neighbours. He had no wish to waste his talents painting a series of great poets' portraits for Hayley's new library, or handscreens for his neighbour, Lady Bathurst. The next year Blake wrote a letter to his patron Butts stating that only in London that he could 'carry on his visionary studies.’”(The Gothic Life of William Blake.) As Blake’s life toiled on he could only see the monotony of his life and his workings and eventually he snapped and gave it all up so that he could actually go out and try to break free of what society wanted him to do. One way or another, his decision to break away from the norm and strike out into a field where his mind could expand relates to another key idea from Gothicism: the break off from the norm.

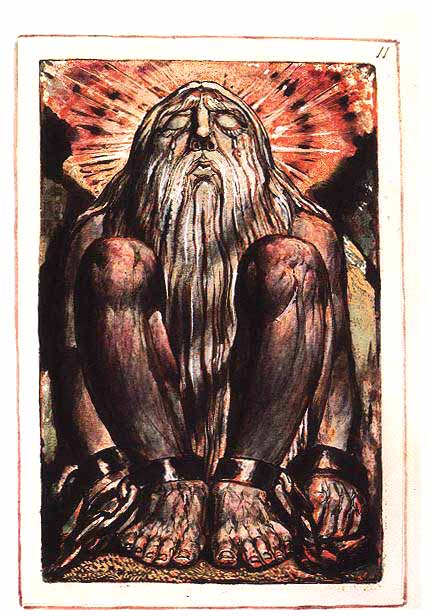

Blake’s next target proved to be the most debatable, and sometimes offensive, topic of all: God. Blake decided he was going to write a series of stories about the formation of the world and the higher powers involved. This series is known as the Books of Urizen. Urizen is Blake’s interpretation of God, where he portrays the mighty Creator as an ultimate power that is chained to its miserable involvement with man. The stories themselves carry a type of monotone to them, one way both Blake and the Gothic style try and show a lack of importance in the creation of the world and an importance on how that world is used. The professed ideas are still important as it portrays God as not the all mighty and majestic but something powerful yet unruly. Several critics agree that this is what Blake was going for. Even this critic, a random female student at a university, concurred that Urizen itself held both power and a lack of majesty: “Blake's The Book of Urizen (1794) tells the story of an "Eternal" named Urizen, a Faustian figure who roils with unarticulated passions and "unquenchable burnings" in the beatific plenitude of Eternity until he is cast out by his fellow Eternals into the Void.” (The Strange Attraction of Blake’s Urizen.) This critic found Urizen to be more of a mighty child with nothing but the world as his plaything. Several critics have agreed on this idea where as others have come to the conclusion that Urizen was intended to be a daunting figure of God that stood for sensibility, probably through measurements and science. Another critic states, “Urizen, clearly representative of God, though not synonymous, was a son of Vala, goddess of nature. Usually depicted in solitude in a cave or on a rock, the morose and wrathful Urizen writes out his laws in books of brass, iron, silver, or gold. Not a positive figure of authority, the name brings to mind "reason," which Blake saw in negative contrast to the power of creative inspiration.” (William Blake Dreamer of Dreams.) This critic explains that Blake was actually “poking fun” at the classic look of God, since he contained no love for anything that might hinder any kind of experience of joy anyone could have. The idea of God as an authoritive yet demanding figure did not settle well with him since he thought all men should be able to stretch their sexual or imaginative freedoms to their full extent. The last hint of Gothicism in Blake was exactly that idea: god is not out to help mankind but to chain him down to His own will. Clearly, Urizen was one of Blake’s methods used to strike out against society. It is clearly evident that Blake was definitely influenced by the Gothic style, even though he wrote in a period of Romanticism. Any of his poems show this through arguments on the meaninglessness of life and death. Other poems of his show certain aspects of love, whether or not they are them positive or negative. His “Books of Urizen” complete the package and give a final few comments on his perspective of a daunting and restricting God. Clearly the Gothic style influenced the Romantic period through authors such as William Blake.

|

||||

|

|

||||

|

|

||||